Shelters of Land and Element

The Flow TripHow Indigenous homes are built with nature

Words by Alexander Kwapis and Dennis Fiore of Wild Dirt

Every shelter tells a story about where it stands. From the chill of the tundra to the warmth of the desert, Indigenous homes rise not as interruptions to the landscape, but as continuations of it, shaped by wind, stone, bark, and intention. These dwellings were never built against nature; they were built with it.

Each is an architecture of respect, an agreement between human and element. Wild Dirt believes that homes speak through the textures of earth, the patience of wood, and the warmth of fire and snow.

Kancha in the Andean Highlands | Inca & Quechua

"Observing and hiking past Quechua villages in the Andes mountains, I felt a connection with its nature." — Dennis Fiore

Photo by Dennis Fiore

High in the Andes, the Quechua people, descendants of the Inca, built homes that breathe with the mountains. In the Sacred Valley near Machu Picchu, Dennis Fiore of Wild Dirt stood and saw firsthand how stone and soil became architecture, shaped to echo the land rather than dominate it. The Inca perfected this idea at Machu Picchu, stacking granite so precisely that walls stand unmortared against centuries of rain and quake.

Roofs once woven from ichu grass swayed with the wind, and sunlight angled through trapezoidal windows, warming rooms carved from the same rock beneath their feet. Today, Quechua villages still follow these patterns, building adobe homes plastered with river clay and crowned with thatch. Each home remains part of a living ecosystem, a shelter that listens to the mountain and answers back in stone and straw.

"In Quechua and Aymara, there is no word for 'nature,' since we do not separate ourselves from it. Rather, we see ourselves as nature." — Sisa Quispe, "Earth Wisdom: We are Nature," YouthToThePeople.com

These are Pucará bulls (Toritos de Pucará), a traditional ceramic handicraft placed on houses for good luck, protection, prosperity, and fertility. This custom symbolizes the blending of Indigenous Andean beliefs with Spanish Catholicism, as the bulls represent strength and Andean traditions, while they are often accompanied by a Christian cross and ladder to represent the fusion of cultures and to ward off evil.

Bandelier Cliff Dwellings | Ancestral Puebloan

In Frijoles Canyon, you can still see the hand-cut ladders and soot-blackened ceilings of long-ago lives. When Alexander Kwapis of Wild Dirt visited Bandelier National Monument, he felt the warmth of the canyon walls as they absorbed the sun's rays and radiated that heat on the cool desert nights. The people weren't just hiding in the cliffs; they were thriving in them.

The National Park Service explains, "The cliff dwellings were constructed to take advantage of natural caves and alcoves in the canyon walls, protecting from enemies and the elements."

These were not simple shelters; they were complex living extensions of the mesa itself. Each room was a chamber of both protection and ceremony, connected by ladders, plazas, and communal courtyards. The wooden rafters (vigas) that supported the upper dwellings, likely built from juniper or ponderosa pine, connected the homes to the forests above, turning architecture into an ecosystem.

The Igloo aka Domed Arctic Shelters | Inuit Communities

The igloo is a marvel of winter survival: Snow is an insulator, ice is architecture, and the human body becomes warm within the cold.

From left to right: Photo by Edward S. Curtis on the Harriman Expedition, 1899 | Photos by Wikimedia Commons

"Although we often think of domed snow houses when we hear the word ‘igloo,’ in reality, the Inuktitut word iglu simply means ‘home.’ In fact, Inuit did not just live in snow houses. Many had sod whalebone homes they used yearly. Summer homes were usually tents made of caribou hides or sealskin." — From Our Land Nunavut: Inuit Ways of Knowing, a teaching resource published by the Museum of Anthropology at University of British Columbia

These homes respond to tundra wind and seasonal drift; they require no imported lumber or metal. The shape of an igloo echoes nature's caves and hollows, offering refuge when the icy world outside is harsh. In modern Inuit culture, while fewer people build igloos year-round, the practice endures in seasonal hunts and in cultural memory, a testament to living with the land rather than conquering it.

Yurt (Ger) | Nomadic Peoples of Mongolia & Kazakhstan

On the sweeping steppe where wind is constant and trees are scarce, nomadic herders erect the round yurt (ger), a collapsible lattice of bent wood and felt wraps of sheep wool.

A ger spacious enough to be home to a family could be taken apart in a short time, packed onto a few strong animals, like horses or yaks, and carried safely to the next home site — a perfect dwelling for nomadic Central Asian peoples who moved several times a year, calling no single place home, but anywhere they needed to.

Inside the ger, the wood has a honey-teak glow, with poles criss-crossing above until they meet the circular crown — both humble and cosmic. Felt blankets the frame; a stove in the center warms the hearth. The design adapts to move with seasons, herds, and families, all meant to travel together. Even today, many families still erect gers on the same steppes their ancestors crossed.

Wigwams of the Eastern North America Woodlands | Algonquians

In the dense forests of the Great Lakes and Northeast, Algonquian peoples built their homes from what the woods offered: saplings, bark, reeds, and patience. Wigwams curved with the rhythm of the forest, shaped not by blueprints but by instinct and relationship.

Inside a wigwam, you might sit under an arc of bent saplings layered with woven reeds or sheets of bark, on mats woven from cattail and willow, and smell the scent of fresh-stripped bark rising at dusk. Firelight flickers across the curved frame, the birch-bark walls breathing softly as night settles in. The design bends but never breaks; flexible, renewable, and built to return to the soil when its time is done. Today, many tribes still raise teaching lodges and ceremonial wigwams to honor this tradition.

Why it matters, beyond the walls

What Wild Dirt has learned from visiting these places and listening to their descendants is that architecture is more than brick, timber, or felt; it's a dialogue with the land. A yurt's lattice answers the wind; a Pueblo's beam echoes the hill; a birch-bark wigwam works with tree and water. Each home listens, adapts, and belongs.

The land teaches what to build: what grows, what floods, what freezes. Every material is local, every design born of need, climate, and respect. These forms still endure in community centers, teaching lodges, and heritage programs: living shapes of identity, carried forward in wood, clay, and memory.

So what about our home here in the present?

Even if the descendants of these communities no longer build with earth bricks or bend willow saplings, the lesson remains: Design with respect, use what the land provides, and let the climate guide you. Imagine how a wall holds warmth, how a roof sheds snow, how a frame breathes. These homes were born of place, not copied, but grown from it.

Oneness stretches across generations, between people and land, into how we sleep, gather, and live. The homes still speak if we listen: the winter wind, the desert dust, the steppe's vast dome. Leave ego behind. Build something that responds.

Wild Dirt was co-founded by lifelong friends Dennis Fiore and Alexander Kwapis, whose bond began in scouting and grew into a shared mission: to explore sustainability, storytelling, and adventure through fieldwork and design. We spotlight Indigenous conservation, build community, and create tools to help others navigate their wild with purpose. Explore more.

An Interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

The Flow TripJack Johnson: The Interview

The Flow TripA Tapestry of Tradition and Tomorrow

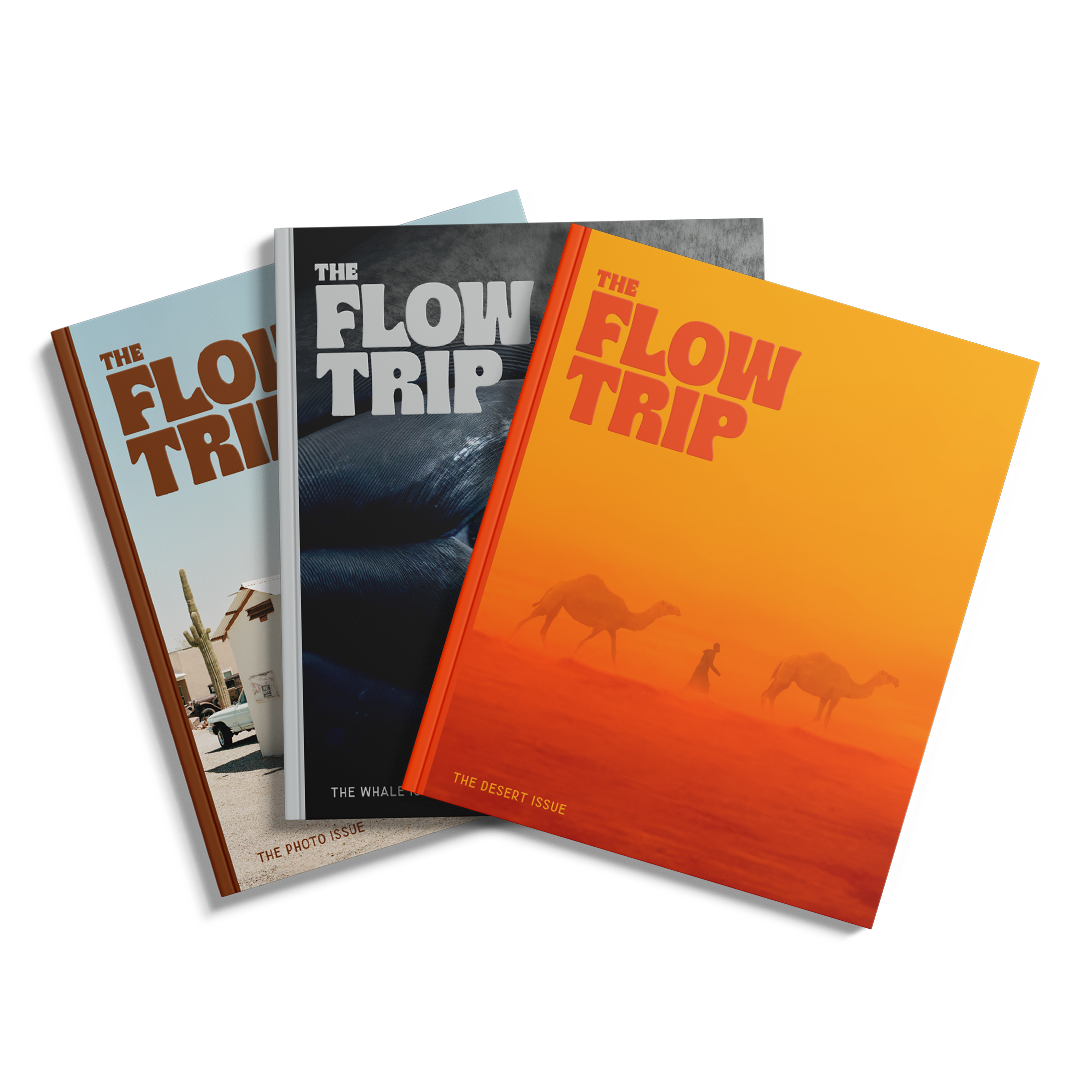

The Flow TripSubscribe to The Flow Trip

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.