Love Behind the Lens

The Flow TripCapturing African American Culture with Shawn Theodore

All photos by Shawn Theodore

There is history all around us, whether we know it or not. Where we live, on our commute to work, in the heart of the city we call home. And it’s the significance of this history that photographer and artist Shawn Theodore works to capture. Focusing on African American culture, Shawn documents the importance of these narratives, with the aim of helping the community understand the past, present, and future of their culture in the United States. We were fortunate enough to catch up with Shawn to explore his journey as a photographer to bring people together, and define legacy.

How do different disciplines in your field of work inform the others, from photography to writing to sculpture?

I really believe in foundation points for all of my practices. The image serves as a foundation, which is really where I like to start. I consider collage to be a form of sculpture in itself, and I’ve always been interested in how small a sculpture can be and how detailed you can go. How do you make something two-dimensional become three-dimensional and allow people to have their imagination wander through the landscapes you create with shape and an image? To me, they are all related because they all have the same origin point. With photography, I am able to begin the process, and it's something that took a while to appreciate. So I think it’s all rooted in the idea that the image can provide so much of a foundation for all of the other acts of your practice that you’d like to see. It’s the magic that surprises you.

What role does legacy play in your work, and how does that shape the stories that you tell?

Legacy is a double-edged sword. Your legacy and the legacy of what you record or what you are taking time to document are intrinsically tied together. You, as the driver behind the lens, have so many options, choices, and things you can create, record, or discover. But you have to have a sense of understanding of what legacy is and why it matters.

I’ve recently been going through all these magazines from the late ’60s and ’70s, and in one issue there is a centerfold of James Van Der Zee, and I got incredibly excited to see this image of him in his splendor and being recognized for who he is. But also, there was this sense of pride in knowing that two steps back, in terms of the people who taught me what I know about photography, were people taught by him. I feel this connection to everything he’s done, going back to the Harlem Renaissance, and that impact of his legacy on culture.

The other part of it is realizing that you don’t have a moment in the photo. Your legacy is put on hold every time you snap the shutter. It’s not about you. You are there in the right place at the right time — in some sort of wonderful quantum way, you have reached this decisive moment to get this image — but it’s never about you. And releasing your ego long enough to capture someone else’s moment to create a legacy around culture — that’s the best you could hope for when you’re a photographer.

Any advice you would give to somebody picking up a camera for the first time?

It’s an interesting thing to get recognized at various high points in the culture. There’s a feeling of being in a vacuum when you’re a creator, and to be recognized by other creators in other genres that see your work and say, “This wouldn't be complete without this work, and we want and need this for our vision.” And that makes you realize the power of art when these things happen. It’s very humbling. It’s exciting, but humbling.

Explain how you felt seeing your work in Tyler Perry’s Netflix show Beauty in Black. What did this mean to you?

It’s an interesting thing to get recognized at various high points in the culture. There’s a feeling of being in a vacuum when you’re a creator, and to be recognized by other creators in other genres that see your work and say, “This wouldn't be complete without this work, and we want and need this for our vision.” And that makes you realize the power of art when these things happen. It’s very humbling. It’s exciting, but humbling.

What is the one thing you want people to take away from viewing your work?

I want them to take away that they are actually in that moment. There is a really interesting beauty in seeing something for the first time, witnessing it, and letting your emotions and feelings react to it. That’s not something that I am doing, it’s something that your soul is doing, I am just the catalyst — making something that I needed to feel, and maybe I can make other people feel connected to themselves, mixed with thoughts and feelings and a sense of connection to the rest of the world. Even parts of our imagination that connect on a deeper consciousness level — I want people to know that you should feel energized and activated, and connected to something greater. It’s that sense of appreciation and consciousness of each other’s imaginations. Just allow for those things to take hold and do something to you. I want them to be triggered into finding that feeling all the time. It’s a beautiful thing to know you can impact people’s lives and make them better.

You coined the term “Afromythology” to help describe the trajectory of your work. Explain how you shaped this idea and how your current work continues to embody this.

It was more of a discovery of absence. I was looking one day and thought, “African Americans… what's up with mythology?” And I had to stop and say, “Well, where did it all come from?” while recognizing that, historically, African American culture is one of the youngest to exist, parallel to American culture. So we have this space, but we don’t have the mythology, and I started to do as much research as I could to discover connections to many of the West African traditions and different folklore bleeding into America, and seeing how that synthesized its way into popular culture. As part of legacy, it's important to note these things, even if they are remote or minute in literature or art. It's important to tie together all of these things to prove one very important thing: Black people are going to be in the future. The deeper you can root yourself in the past, be it speculative or real, as long as the roots are going deep, you have an opportunity for a lot of growth in the future. Afromythological work is all speculative; it’s all what most people would call inceptual work, but when you guide conceptual work with an idea of mythology, spirituality, and a real sort of zeal to tell stories without telling people what to do, you can really accomplish a lot. The important thing is to ensure it reaches the culture and that the culture is inclusive, allowing anyone to participate in the African American present, past, and future, as well as speculative futures and pasts.

One photo of yours that tells the best story.

When I was making the image Kingdom, the sun was leaning low, casting that kind of hush across the block that wraps a moment in meaning before you even know it’s begun. I stood still, camera raised, waiting for the light to speak. That’s when he approached — a young man, in his mid-twenties, his fiancée beside him, their child tugging at his hand.

He asked, “What are you doing?” Not out of simple curiosity — he was really asking, What are you searching for?

I told him I was creating something new. Gathering images the way others gather names, memories, and prayers. Trying to catch what gets lost when we stop paying attention. He nodded and said, “That sounds like something I need to be a part of.”

We stayed in touch. Quiet questions followed — about light, framing, and how to tell a story without shouting. Then came the images. His. Honest. Unguarded. Still trembling with belief.

Later, he told me that seeing me that day felt like permission; like someone had left the door open.

Now he speaks in his own visual language. The work doesn’t whisper anymore — it testifies.

Some moments are seeds. Some images are maps — for people we haven’t even met yet.

An Interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

The Flow TripJack Johnson: The Interview

The Flow TripA Tapestry of Tradition and Tomorrow

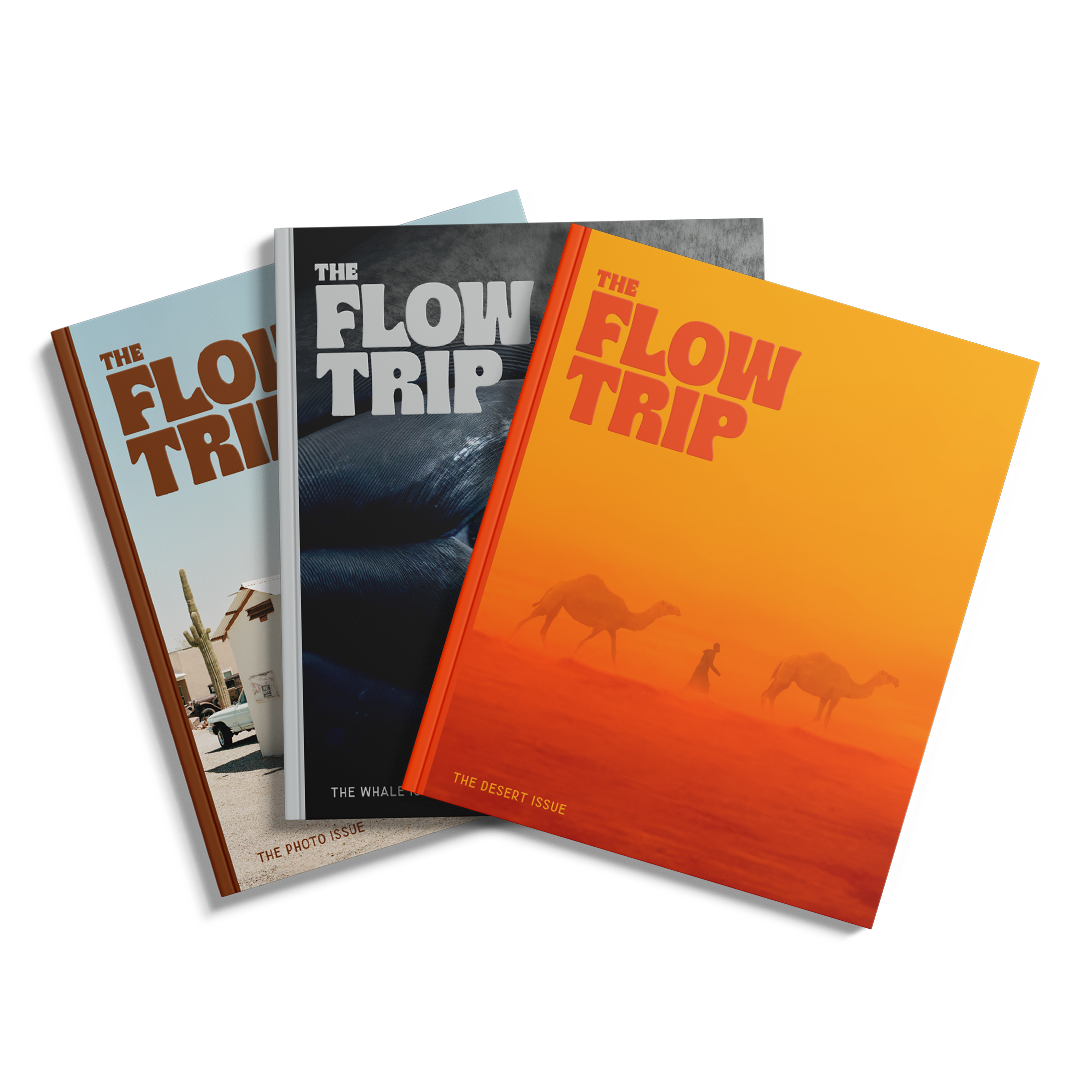

The Flow TripSubscribe to The Flow Trip

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.