The Great Trek

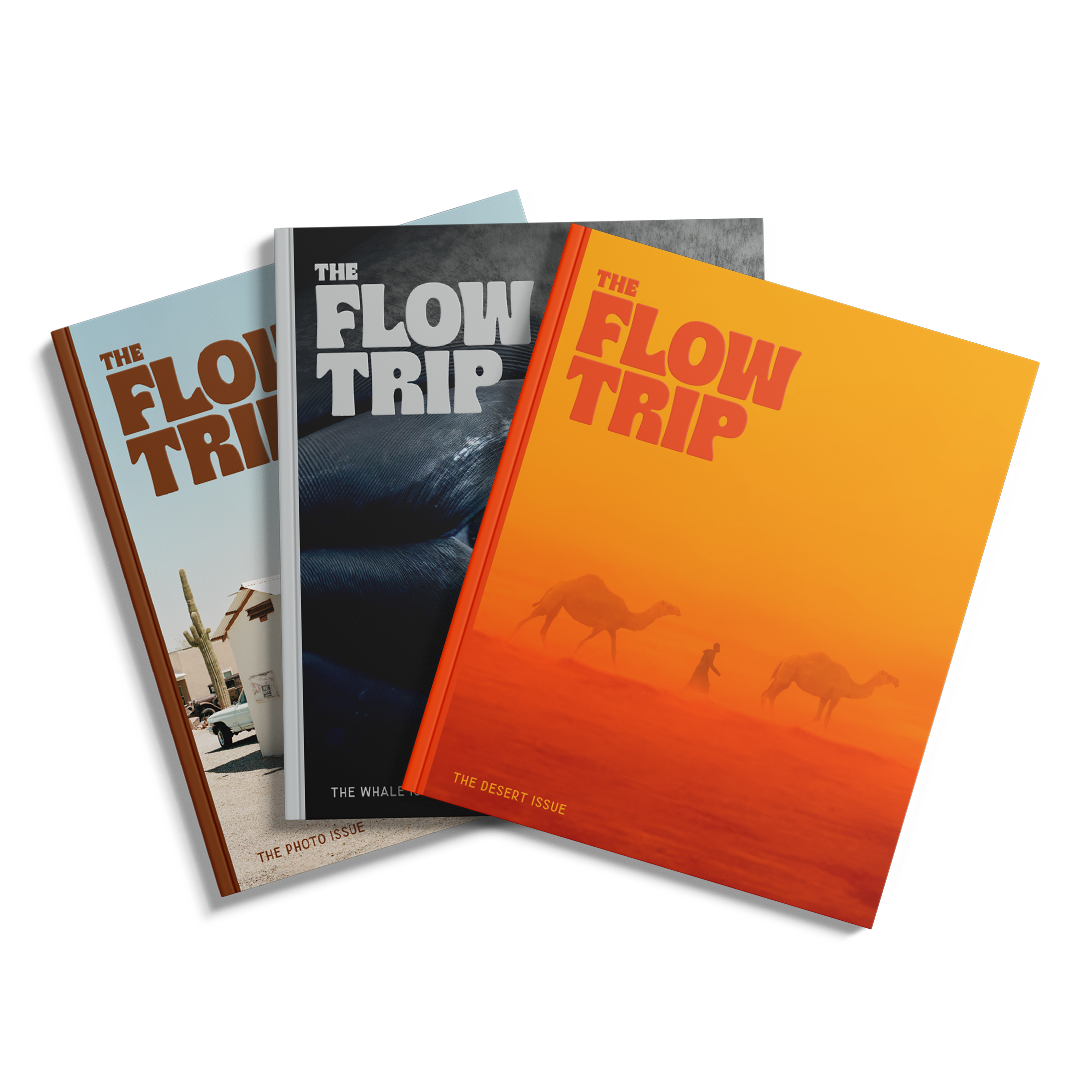

The Flow TripA glimpse at animal migration

Darwin didn’t call it “survival of the fittest” for nothing. And with that instinct comes an innate drive to do whatever it takes to stay alive — including traveling thousands of miles by foot, air, or sea to find fairer weather, bountiful food options, and their mate. Animal migration is something scientists avidly study to understand the nature of animals, how we can avoid impeding on their paths, and ultimately, how these animals innately know where they need to go, whether it be across oceans, continents, or countries.

![]()

Name: Chad Witko

Title: Specialist, Avian Biology, National Audubon Society’s Migratory Bird Initiative

Bio: Before coming to Audubon in 2019 to help secure the future of migratory birds in the Western Hemisphere, Chad had worked for fifteen years on various avian research, conservation, and education projects across the United States. A lifelong birder with strong bird identification and distribution knowledge, Chad serves as an eBird reviewer and on the Vermont Bird Records Committee. As an ornithologist, he is most interested in migration, patterns of vagrancy, and seabirds.

Bicknell’s Thrush | Catharus bicknelli

Bicknell’s thrush is a rare, secretive songbird that breeds in the high-elevation and maritime forests of the Northeastern US and Southeastern Canada. Nesting in fragmented montane habitats dominated by balsam fir, these relatives of American Robins are long-distance nocturnal migrants that winter exclusively in the Greater Antilles, primarily the Dominican Republic, where males and females segregate by elevation and diet. Rarely observed during migration, light-level geolocator data reveal complex routes with key stopovers in the Southeastern US and the Caribbean. This species is a top conservation priority due to its limited range, specialized habitat, and ongoing threats.

Hudsonian Godwit | Limosa haemastica

Once considered among North America's rarest birds, the Hudsonian godwit was overlooked for decades due to its remote breeding sites and astonishing long-distance migration. This elegant shorebird nests in scattered subarctic wetlands from western Alaska to Hudson Bay before embarking on a remarkable journey to South America. In fall, most fly nonstop from the south end of Hudson Bay to Argentina and Chile, wintering on key coastal mudflats and pampas marshes, including Chiloé Island, where up to 27 percent of the global population — and 99 percent of the Pacific population — winters. Spring migration follows an inland route through the Great Plains. Protecting wetlands across the Hudsonian godwit’s range is vital to its survival.

Explore more at Bird Migration Explorer | http://birdmigrationexplorer.org/

![]()

Name: Dr. Chris Lowe

Title: Shark Lab Director, California State University, Long Beach

Bio: Dr. Chris Lowe is a professor of marine biology at California State University, Long Beach. After finishing his doctorate in zoology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, he became the director of the Shark Lab in 1998 and has spent his career studying the behavior of sharks, rays, and gamefish using novel technologies.

Great White Shark | Carcharodon carcharias

Even as newborns, the great white shark, also known as the white shark, can surely get around. While no one knows where they are born, they often show up at Southern California beaches soon after birth, to hang out in the safety and warmth of the shallows. Many will spend their first summer cruising the waters just off the beach, learning how to catch food like stingrays and looking out for predators. However, when the water temperature drops and stays below 60 degrees Fahrenheit, they head south, with some sharks migrating all the way to the Gulf of California for the winter. Many then trek back to Southern California the following spring, traveling over 3,000 miles in their first year. Other than just being cold, we really do not know why they do it, how they decide where to end up, and what drives them to come home.

Gray Whale | Eschrichtius robustus

The Pacific gray whale is another seasonal traveler, exhibiting the longest annual migration (more than 10,000 miles) of any mammal. Born in lagoons along the coast of Baja California, calves and their mothers will start their coastal journey north beginning around late February, with some arriving in the food-rich waters of Alaska by early April. In the fall, they will migrate south back to the lagoons to mate and give birth. So, why swim all the way to Alaska? It’s all about the food — they’re feeding all summer long so they can make their southern migration and overwinter in the lagoons of Baja.

![]()

Name: Dr. Jared Stabach

Title: Research Ecologist, Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute

Bio: Jared is a research ecologist at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute and the terrestrial lead for the Smithsonian's Movement of Life Initiative. His research focuses on the factors that affect the abundance, distribution, and movement patterns of large terrestrial mammals, with a specific focus on African landscapes.

Masai Giraffe | Giraffa camelopardalis

Giraffes are often overlooked as a migratory species. Giraffes, however, move across international borders to access gradients in environmental productivity, fitting one of the requirements of the Convention on Migratory Species to be considered migratory. Little is known about the movements of the world’s tallest animal, but researchers have fitted some with devices on their ears and tails to increase our understanding of each species' space-use needs; this is a less invasive alternative to traditional GPS collars. Northern and southern giraffes are known to move more per day and have larger home ranges than Masai or reticulated giraffes. The total giraffe population throughout Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be just 117,000 individuals, with habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching, and disease being the primary reasons for species decline.

Blue Wildebeest | Connochaetes taurinus

Wildebeest take part in one of the last remaining terrestrial large mammal migrations on Earth. Moving in a clockwise pattern, approximately 1.3 million wildebeest migrate with herds of zebra, eland, and Thomson’s gazelle in response to seasonal rainfall gradients. Beginning in the nutrient-rich short-grass plains in the southern Serengeti, wildebeest give birth to a single calf. They move west and northwards as seasonal rivers run dry and forage becomes scarce, moving to their dry-season refuge in Kenya in early July and August. Wildebeest then return south in September and October before starting the annual journey once again. The migration of the wildebeest is threatened by a lack of access to water, with linear barriers such as livestock fencing and the expansion of agriculture significantly restricting animals from accessing traditionally used areas, especially in times of drought.

See the full profile of the project at https://movementoflife.si.edu/

Learn more at the Giraffe Conservation Foundation

For more migratory information, visit the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration

Feature image by Vincent Van Zalinge | Unsplash

An Interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

The Flow TripJack Johnson: The Interview

The Flow TripA Tapestry of Tradition and Tomorrow

The Flow TripSubscribe to The Flow Trip

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.