Talking to the Scientist who Talks to Whales to Talk to Aliens

The Flow TripWords and Whales by Avery Schuyler Nunn | @earthyave

For some scientists on the quest to communicate with aliens, the most promising path doesn’t begin at a telescope aimed at the stars, but rather, in Alaska’s Frederick Sound. That’s where renowned astronomer Laurance Doyle and his colleagues at Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative) had a 20-minute conversation with a humpback whale.

In an encounter that would make Captain Kirk and Spock proud (remember the time they time-traveled to talk to humpback whales and save the Earth?), the research team broadcast three sequences of humpback calls, which were recorded the previous day, through an underwater speaker. A female humpback later nicknamed “Twain” approached and responded. And not just with any sounds, but with nearly identical calls that maintained the same timing shifts over a 20‑minute, 36‑call exchange. The researchers interpreted this precise call‑and‑response as evidence that the whale recognized the boat as the sound source and was actively engaging. They left the encounter wide-eyed and buzzing, having witnessed a rare, possibly foundational step toward two‑way human–cetacean communication, an insight they described as both scientifically significant and incredibly emotionally exhilarating.

Laurance, a principal investigator at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute, has done everything from bouncing humpback whale songs off the moon to decoding language between plants and insects. Understanding how to detect and interpret nonhuman intelligence, — like a whale responding to recorded calls using matched timing — may help prepare scientists for recognizing and decoding potential extraterrestrial signals, which may follow similar patterns of structured, intentional communication. Just like Star Trek, but with fewer Klingons and way more carefully annotated spreadsheets.

Drawing from information theory, a mathematical framework used to quantify and analyze communication systems, Laurance intends to classify and quantify patterns in nonhuman communication — both terrestrial and extraterrestrial — to determine if a signal bears linguistic structure. As he puts it, “We’re trying to get on the outside of nonhuman intelligence… so that when we get an extraterrestrial signal, we’ll know what to do.” The challenge, he argues, is not just about making contact with other beings, but about expanding our own perceptual bandwidth. Because if we fail to recognize the intelligence already around us, it’s no surprise that the universe feels silent.

We sat down with Laurance to talk about whales, aliens, and why the key to saving the planet might just start with learning how to say “Sorry, our permit’s up” in fluent humpback.

ASN: Do you think that Twain would be a good Earth ambassador Earth to aliens?

Laurance Doyle: Twain showed so much curiosity. The only reason we stopped our exchange was because our permit only allowed us to transmit with her for 20 minutes. At the time, we didn’t know how to say, “Sorry, Twain, we gotta break this off because of our governmental permit,” but she wasn’t done. She started to move away when we ceased to respond, but every 41 seconds transmitted several “Hellos?” which were kind of heartbreaking not to reply to. I think that Twain’s curiosity and willingness to hang in there and communicate with us would make her a really neat Earth ambassador.

ASN: Why do you think that we as humans are so driven to make contact with anything, whether across species, time, galaxies?

LD: I think we want to know where we fit in, whether it’s extraterrestrials and how we fit into the universe or galaxy, and where we fit in on Earth. And I think there’s a spiritual component to getting along with all species and all of creation. In the West, we’ve had this artificial way of keeping spirituality and science separate. But why? People say they’re separate things, but they aren’t separate. Why would we separate nature from sacred? It’s togetherness. And even everything in science points to that. Ecology is built on biology, which is built on chemistry, which is built on physics, which is built on quantum physics — and quantum physics tells us that everything is attached and entangled together.

ASN: Will learning to communicate with whales make us better humans, or create a better planet? Is there anything in terms of conservation to be gained from speaking with whales?

LD: Definitively. Yes. It will make us more respectful of their intelligence. No one I know who has started to study animals or plants says, “They’re dumber than I thought when I started.” It never goes that way. Indigenous peoples have always had this respect for various nations and species, and this can bring us closer to that knowledge. It will bring us closer to a necessary appreciation of the environment and the fellow inhabitants of this planet — and we have really underestimated their intelligence in Western civilization. And in conducting these conversations scientifically, it makes our findings more robust; people tend to argue less with scientific conclusions, because the data is ultra careful.

The more you study humpback whales, the more respect you have for them. And what if we eventually learned the words in humpback for “Get out of the way”? That could reduce ship strikes like crazy. Ship strikes occur way too often, and we’ve been ignoring the intelligence of whales in this case. We know how to say “Hello,” and we think we know how to say “Goodbye,” and I think they would certainly understand a “Move out of the way, a ship is coming.” There’s gotta be a word for it or a series of vocalizations for it, and that’s just one example of how this work can be ecologically applied. We’re working on it, so stay tuned.

ASN: In this ignorance of their intelligence, do you think Twain or other humpbacks ever give us an eye roll of sorts, or a fluke slap in their case, for being slow on the interspecies communication uptake? And since so much of your work is about listening — to songs from whales, voices from elsewhere on our planet, and possibly from space — is there something we could be missing by being such a loud species ourselves?

LD: We certainly need to do more listening as a species. The idea of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence has dawned a version of this, but it’s possible that whales have been trying to communicate with us for a long time on our own planet, and we just haven’t paid attention to it. We spoke to Twain in Twain’s language, in what we hypothesize was a greeting call that we had recorded the day before, but what we’re not sure of is whether it was Twain’s own voice recorded, so it might’ve been an acoustic mirroring. It’s possible that in our exchange, we didn’t respond in the most intelligent way. We didn’t stick our heads in the water and try to directly communicate, because we were too blown away. We did not respond as intelligently as Twain did to us trying to speak humpback, and we do not respond as intelligently to a humpback trying to speak human. We have a lot more research to do, and we as humans are not the smartest ones on the block in this conversation.

ASN: If you could beam a whale song into space to represent Earth, what kind of call would you choose?

LD: I have transmitted humpback into space! When you warm up a radio telescope transmitter, you just use any files that you can transmit to warm it up. I decided to transmit some humpback whale. And so, I bounced a humpback whale song off the moon!

ASN: What feels more “alien” to you: a distant exoplanet, or the inner workings of a humpback's mind?

LD: I hate to be predictable, but I have to say the exoplanet. We’re mammals with humpback whales, and we're familiar with water as a medium for communication. And humpbacks, for some unknown blessed reason, communicate within our range of hearing. You wouldn’t expect that, given that they weigh, like, 500 times as much as we do. On the other hand, all I had to do was have a humpback whale breathe near me to become struck with this incredible sense of intelligence, coupled with a nonhuman, alien creature.

ASN: If we could communicate anything we wanted to Twain, no matter the complexity or syntax, what would you most want to say to her?

LD: Well, I think it would be describing our own species to each other. If I had a message to get across to Twain, it would be that there are a large number of humans who care for and love humpback whales: “We want you to know that there are indeed humans who are consumed with greed and just don’t think of other species, but there’s a large and increasing component that cares about you and your life in the ocean, and we’re doing our best to make that the majority of people. Our encounters with you can help us educate others in order to create that love, and create healthier oceans through that love.”

An Interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

The Flow TripJack Johnson: The Interview

The Flow TripA Tapestry of Tradition and Tomorrow

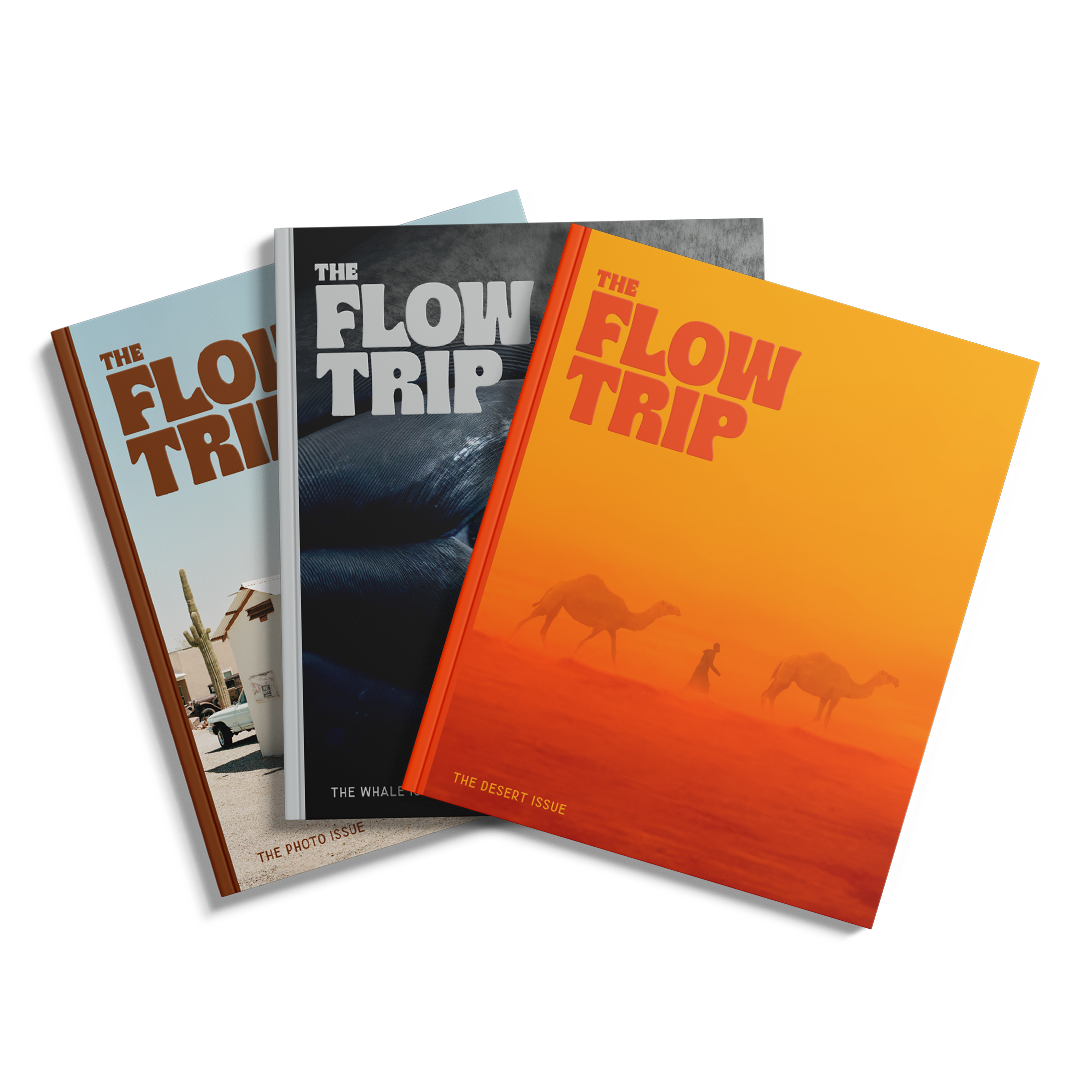

The Flow TripSubscribe to The Flow Trip

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.