Parallel Universes

The Flow TripInto the depths and outside the atmosphere with scientist, astronaut, and explorer Kathy Sullivan

Only one person on Earth gets to say they were the first American woman to ever leave a spacecraft. And that person is NOAA administrator and former NASA astronaut Kathy Sullivan. But she didn’t stop there. Curiosity is a superpower that has driven Kathy to look beyond our own planet and deeper into it. And as the first woman to dive into Challenger Deep, the deepest known point of the Earth’s floor, Kathy continues to traverse the unknown and push the boundaries of exploration as we know it.

Flow Trip: Explain how you felt when you first exited the Earth’s atmosphere.

Kathy Sullivan: The thing that strikes you most when you launch on a spaceflight is that you don’t even notice the moment you leave the atmosphere, it happens so quickly. But what you do notice is the moment when the rocket engines stop thrusting you upward and suddenly everything is essentially weightless. Your pencil will float, your book will wander around at the end of its tether, and your first glimpse out the window at the Earth, now hundreds of miles below, takes your breath away.

FT: What parallels do you see between outer space and the depths of the ocean? From a scientific perspective and an exploration perspective?

KS: To me scientific, technical, and explorative are completely intertwined, they’re not separate things. The key similarity is the caliber of engineering and manufacturing it takes to send people safely into either of those environments. To go into the sea or to go into space, you’ve got to make sure that whatever craft you’ve designed will provide the human beings inside with the right kind of atmosphere to breathe, the right kind of pressure, and that it can maintain the fairly narrow range of temperature that we are adapted to.

One of the big differences is when we’re going to space we have to deal with a fairly small pressure change, from the pressure at sea level to effectively no pressure outside your window.

When you explore in the deep sea, the pressure continues to increase down to the maximum depth of the ocean. In fact, every 10 meters or roughly 33 feet, you’re adding the equivalent of the weight of a whole atmosphere on top of you, so it’s common to talk about the depth of the ocean in terms of how many atmospheres you are at. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, you’re at 1,000 atmospheres. (For reference, the Earth's atmosphere is estimated to weigh around 5.5 quadrillion tons.) So you’ve got to keep a thousand atmospheres outside of the vehicle so you don’t squish the people.

"We have in some ways explored more of space than we have the deep sea."

FT: And how about the parallels regarding the unknown? The fact that humans are at the beginning of understanding both of these environments?

KS: We have in some ways explored more of space than we have the deep sea. In a lot of ways, it is harder to explore the deep sea. In space, you can use light, lasers, radar, and signals to probe or explore the nature of a planet or asteroid. All of them transmit easily through the vacuum of space. But none of them transmit through water. The kind of mechanisms we use for remote sensing even the surface of the earth, much less the surface of Mars or the moon, don't work in the ocean.

So it becomes a much more difficult sampling and exploration problem. It’s not too much of a stretch to say you can only understand what lives in the ocean by bumping into it, by getting up close and happening to see it, which is a very tall order considering the volume of the ocean.

We think of the ocean as large because we see a big expanse of blue on our maps, but it's really the volume of the ocean that is daunting to understand. And certainly, it’s a huge challenge to understand the full array and abundance of life in the ocean. When we think about the vast expanse — the deep sea, rain forests, the Central Asian steppes, or big tracts of terrain — the bulk of the habitable volume on this planet is the ocean. And the bulk of the biomass of this planet is in the ocean.

FT: What fueled you to want to explore these two extreme environments?

KS: It really is, truly from as young as I can remember, what I tend to term just a “geographic curiosity.” You know — what people, places, planets, economies, or societies are where? How do they work? What are they like?

That’s been the most active thread in my imagination and curiosity from early childhood. Starting with things like stealing the map out of every issue of National Geographic that came to our house and poring over all the details, all the stories. Those maps in particular were all storytellers — you could glimpse a lot of the stories of a place by just poring over the text on those maps. It continues to this day, being curious about things like that.

FT: And how can exploring one environment help us better understand the other?

KS: I would add a dimension to that answer. I think exploring either of them, at any scale, even from a simple, little bit of exploration in your neighborhood, first and foremost transforms us for the better — sharpens our senses, sharpens our power of observation, and hopefully whets our curiosity. Exploration is any time you put curiosity into action. It doesn't have to involve expensive airline tickets or marquis headline-making destinations. The power of exploration attunes us more keenly to the world around us, the people around us, and the places around us. I think that’s really the crossover between them — continuing to build your mental muscle to engage and find ways to deal constructively with the unexpected and the unknown.

"I don’t think it’s any exaggeration to say that there is no living thing of any sort, in any place, on this planet to which we are not in some way connected."

FT: Do you believe aliens came from underwater? Why?

KS: There are definitely life forms in the ocean that we have yet to discover. We discovered an entire ecosystem in dark, superheated, acidic waters in the deep ocean in the mid-1970s. No one had any idea such things could exist. In fact, school textbooks at that time would have made it very clear that no such things could exist. Except they did. Right here in our own Pacific Ocean. That’s where we first found them and later found variations of this same kind of ecosystem in other places. So if you’re thinking “alien” means, “I haven’t seen it before, so it’s weird to me,” then those are definitely alien life forms. If you’re thinking of something that cruises up in a speedboat or spaceship and has a business card, that’s very unlikely.

FT: How have your experiences in both of these environments helped shape your view on environmentalism, the care of our own planet?

KS: A common thread between the two is how interconnected every place and every living thing on this planet is. I don’t think it’s any exaggeration to say that there is no living thing of any sort, in any place, on this planet to which we are not in some way connected. We’re very aware of some of the connections, and there are countless others we don’t recognize or are too subtle for us to perceive.

FT: What was the purpose of your trip to Challenger Deep? What were your takeaways from this expedition?

KS: I was part of a larger set of expeditions that Victor Vescovo and his group called Caladan Oceanic mounted in 2020. But from the beginning of that effort, his real goal was to unlock access to the deep sea for scientific exploration and discovery. So with the adventure part completed in 2019, from 2020 through 2023 he mounted and self-funded a set of deep-sea campaigns with a surface ship, submersible, and three robotic instrumented packages he calls landers, which could be put 36,000 feet down on the seafloor in these deep trenches and can hold different scientific equipment like water sampling flasks, flow meters, cameras, etc.

So the big objective Victor set for our leg of this campaign was to radically refine the precision of measuring the deepest point of the Challenger Deep. Before that expedition, you could find a published number for how deep it was, but that would be plus or minus about 160 feet. Its depth was always a range from 35,600 feet to 35,900 feet. Victor wanted to get that range down to a single-digit number. That involves careful planning with a lot of instrumentation on the landers on the submersible and the surface ship, and a lot of mathematics to correct for all of the technical aspects. Sam Greenaway, who I worked with on this, clocked in all that data, analyzed it, did the math, and got it down to plus or minus about 19 feet.

FT: How did going to the deepest accessible part of the ocean make you feel?

KS: Intellectually it felt a lot like getting into space. Obviously you’re not floating around inside the submersible, but I had a similar sense of wonder in both environments. It’s kind of magical to be able to sit inside a space shuttle or a submersible and to be dressed like I am here at my kitchen table and feel completely normal and at home, and right outside the window is an extraordinary environment that you know you could not survive in. It’s fascinating and wild that the boundary between sipping your coffee or eating your sandwich and a lethal environment is just that window. It’s magical to be able to be in those places and really experience what they’re like and what they show you. But even with all that said, you are very mindful — the pilot and engineer in me are very aware of the craft around me. That background alertness is always present.

An Interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

The Flow TripJack Johnson: The Interview

The Flow TripA Tapestry of Tradition and Tomorrow

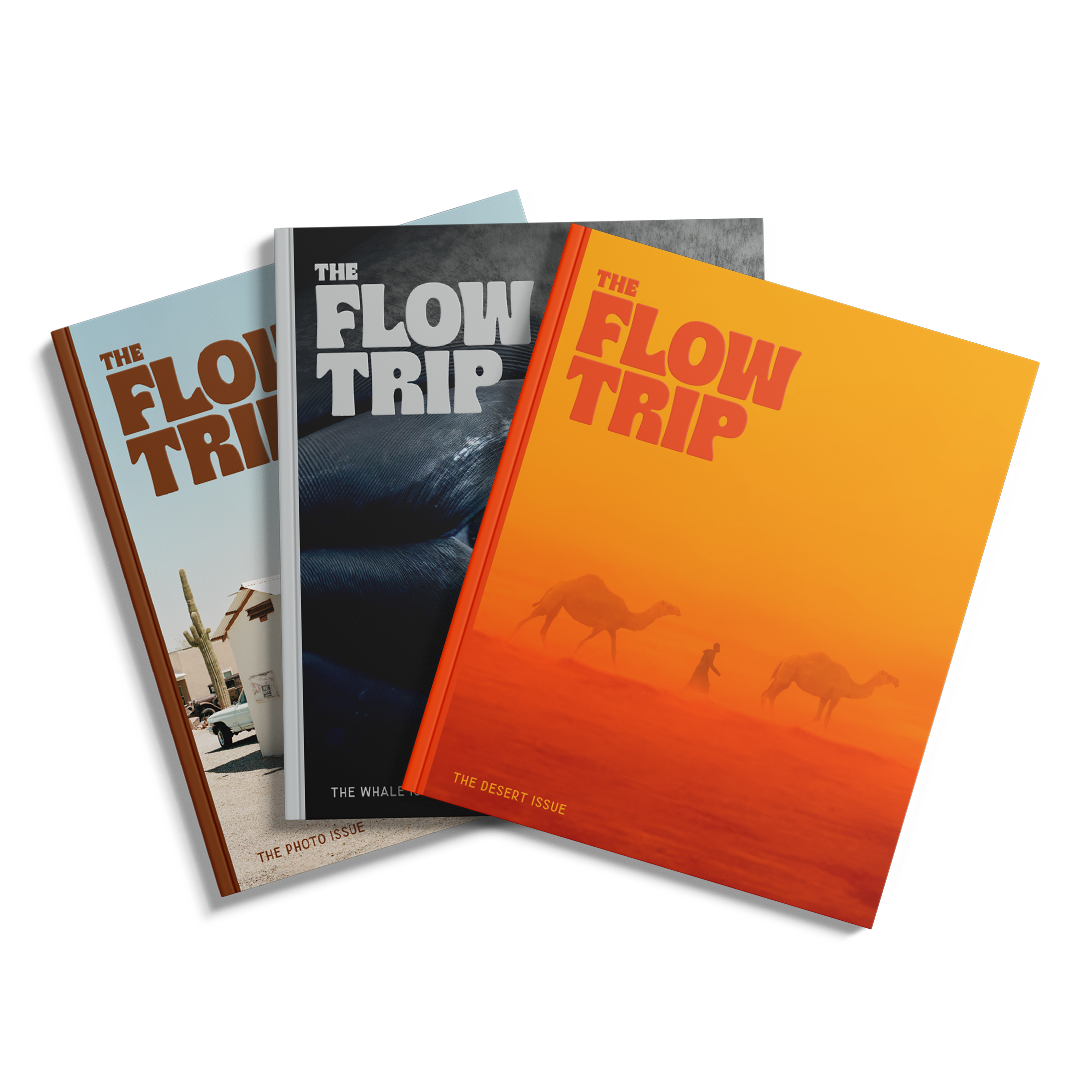

The Flow TripSubscribe to The Flow Trip

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.